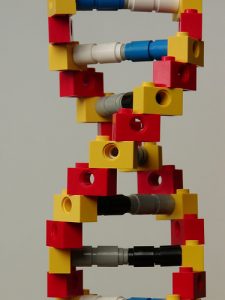

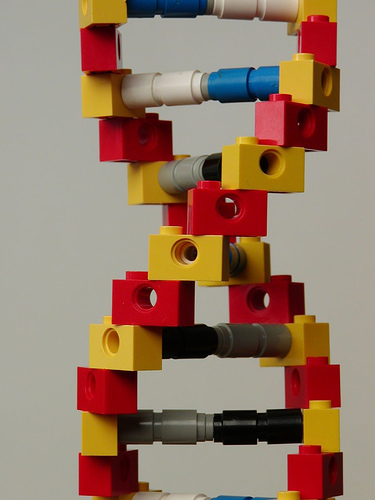

Credit: mknowles

As a teacher working with at-risk students, I love the advantages of kinesthetic learning. In fact, my students thrive on being hand’s on, and it’s not just because they’ve struggled in a traditional classroom previously. My group of at-risk students are those who meet certain criteria that make them more likely to not succeed in the traditional sense.

My students have everything from ADHD and bipolar disorders to homelessness, teenage pregnancies, criminal backgrounds and substance abuse issues. These are not students who sit well in a quiet row taking notes when it comes time to learn about Julius Caesar. They are the embodiment of all of our frustrations in school – they love to challenge the teachers and they have no intention of doing any extra work on their own. It’s all on me to get the information to stick in their minds the majority of the time.

Having this tough crowd means teachers like me can’t use the time-tested (if boring and marginally effective) methods so heavily favored by most secondary teachers. The old lecture/notes/test framework is out for me, but I still have to get the same amount of information into the minds of my students without using lectures they won’t listen to, homework they won’t do or independent study they’ll just talk through. Teaching outside the traditional teacher box means you need an entirely new bag of tricks, and among my many different techniques, using kinesthetic learning is by far the most effective.

Why?

Generally, because kids today want to be entertained. Their entire experience is comprised of stimulation – games, television, music, computers, lifestyles. They have to literally shut themselves down to come to school, and for many, especially mine, they simply can’t. These are very bright students who often struggle with tedium and boredom more than anything else. Kinesthetic learning works by letting the students get engaged in the learning process and by almost forcing learning on the unsuspecting student. The best way for a stubborn child to learn is when they don’t actually realize they are learning.

There has been a great deal of discussion in the educational community about brain-based learning and kinesthetic learning, which for all intensive purposes overlap very heavily. Yet even though everyone knows this is a good thing, it just isn’t used in many classrooms. Having worked with teachers of all ability levels – some good and some bad – it’s clear to me why kinesthetic learning doesn’t happen nearly as much as it should.

Teachers don’t know how to run a hands-on classroom. When I was working toward my first round of teaching certifications, I was taught the then-proper way to do a lesson plan. It went something like this: Introduce lesson, teach lesson, guided practice, independent practice, review, assess. While solid enough to be nicely flexible to those of us who like to experiment, most teachers adhere to this method like a religion. They were told to preach and assess and by-golly, they do! Many teachers, especially those who have not worked with the later forms of lesson planning and collaborative learning simply don’t realize this is an almost antiquated format if taken too literally.

Teachers aren’t able to let go enough to try. I’ve taught in a few different ways and even tried lecture and hard discipline once upon a time. It didn’t suit my style, but it was far easier to stand at the front of the room, talk about the subject, have the students take notes, and then assign the work for them to do. It’s straightforward, and running a tight ship means you have control of all behavior all of the time. While structure is certainly worthwhile, you have to let go a bit to let students experiment with the lessons and make a mess playing around the concepts and ideas rather than taking neat notes or pretending to take neat notes.

Teachers don’t believe it works. Unfortunately, there are more than a few teachers who simply don’t think letting students do projects and apply information is beneficial to learning. These teachers often struggle with the general concept of project-based learning and feel like projects are a waste of valuable lecture time.

Teachers don’t like catering to wayward students. For some teachers, the problem is not with their instruction that has worked so well for decades, but the students. Students today aren’t as disciplined or dependable as they used to be and catering to those students by entertaining them is akin to blasphemy. School is not designed to be entertainment – it’s education and the students should be working harder. End of story.

Unfortunately, many of these teachers don’t take into account how many more students today are staying in school when they would otherwise be dropping out. While some of us try to keep students from falling between the cracks of the educational system, these teachers do all they can to force the students out who don’t fit their particular educational model.

Despite those who are adamantly opposed, like all things in education, there is a gradual shift underway. The classroom is moving from the staid lecture model to the more collaborative, project-based method of learning. This is true not only in the high school classrooms, but in many college classes as well. While it’s impossible to turn a 300-student lecture into project fun, many of the smaller classes at the university level are becoming increasingly hands-on to appeal to the modern learners and indeed the new (and improved!) workforce that is being cultivated as creative thinkers who like to get their hands dirty – both figuratively and literally.